Is it a bit grandiose to quote yourself in the sub-heading? Probably. But screw it.

Simple aim today - why does the U exist? And why does simply knowing why it exists help us make it a bit better?

I mean, on the surface the U-shape (read this if you don’t know what I’m talking about!) isn’t rocket science - in middle age, you’ve got a stressful job, bills to pay, maybe some kids, ageing parents, your health may be on the decline and you’re coming to terms with your own mortality. Of course happiness is going to be low.

But why does it get better after 47 when our health should be getting worse? And why, when clever stats folk strip out the impact of all those things above (money, health, kids, job etc.), do we still see the U shape everywhere in the world?

Most the content that follows comes from a book by Jonathan Rauch called “The Happiness Curve” (where he does a cracking job of summarising all the scientific literature on the topic - give it a read!)

Don’t get me wrong, all of those things above - money, health, kids, job - are all going to be fertile territory for our U-screwing experiments. They have a huge impact on happiness for the individual. But today, we’re going to look at people in aggregate to try and understand why the simple passage of time seems to create the U-curve and, with that understanding, get some clear actions to try and change it.

Good news, I’m pretty sure that simply understanding why the U-happens, could make it less a severe for you. Now that’s worth a read isn’t it?

As I wrote this, it got long, so I’m going to split it in two parts (and maybe get AI to summarise it for me after!) but the key takeaways are going to be:

(1) Compound disappointment - it’s likely you’re not achieving younger you’s dreams, and this disappointment compounds over time. You also probably don’t actually care about those dreams so if you did reach them, you wouldn’t be happy anyway. Time to reset those expectations & focus on what you do care about.

(2) Neuro treadmills - even if you’re married to a Beckham and living in a mansion, you’ve probably now got your eye on a Reynolds & a palace. That’s not your fault, it’s evolutionary biology. Good news is, like Snowdon says, brains are for hacking too. Let’s do that (to be clear, I mean brains, not classified docs in case anyone from the CIA pops in for a snoop)

(3) The doom loop - you’re probably pissed off that you’re pissed off, particularly if you’re “objectively fortunate”, and this will be making you less happy. Simply knowing this is perfectly normal can stop the downward spiral. It’s OK to not be happy. You’re OK. It’s normal.

We’ll cover number (1) here as it has a chunky intro to the theory, then dive into (2) and (3) next time.

Compound Disappointment

What did you want to be when you grew up? If you’re anything like me (or Scherzinger et al.) it may well have involved fame, movies, seeing the world & some groupies. It probably wouldn’t involve sitting on a packed commuter train writing about why most people my age are miserable!

Well, fortunately a chap called Hannes Schwandt decided to put some science behind those profound Pussycat dolls lyrics (and happiness more broadly).

With this in mind, Hannes dived into some beautiful German time series data that tracked actual (i.e. happiness today) and expected (i.e. happiness in 5 years time) data from 1991 to 2004. Here’s what he found…

So what does this tell you? Really simply, all through your 20s, 30s & 40s you end up being less happy than you thought you’d be 5 years before. You’re disappointed. Then, as you get older, the level of disappointment reduces as you become more realistic. Finally, the graph flips. Mid-to-old age (on average) is simply less rubbish than you expected, so you’re pleasantly surprised.

What’s even more interesting is that these two lines aren’t just correlated, they’re causal in a number of ways. Let’s talk regret & optimism.

When your expectations are unmet, you’re disappointed. This gap between expectations and reality as you go through your 20s and 30s then causes a reduction in satisfaction. What’s more, the science shows that this disappointment is cumulative - you’re increasingly dissatisfied that life hasn’t turned out as expected, you have regret. We’re not talking specific regrets here (like having that 4th cocktail at dinner last night), but regret as the cumulative gap between expectations and reality.

What’s more, you start to rebase your expectations and this compound disappointment lowers your future expectations of happiness. This recalibration happens as you travel through life (i.e. move along the x-axis). Given that, as time gos on, an increasing proportion of you life has happened, there’s then less time and less scope for the fundamental change in your remaining years. Optimism wanes (aided by our expectation of our later years being a bit rubbish due to deteriorating health) and happiness with it.

As the chart shows, this depressing combination of cumulative regret and waning optimism collides to create the happiness trough in your 40s. Bleak eh?

But the good news is, we overcorrect. In our late 40s (on average) our realities outperform our expectations. We over compensate and lower our expectations too much - meaning the realities of later life are typically a pleasant surprise & we get happier into our 50s and beyond.

But who wants to wait for that? My view is that if we want to pull up the bottom of the curve as we head into mid-life, we need to understand why there’s that expectation gap and work to narrow it.

Why are we getting it so wrong?

So much of happiness and happiness hacking will come back to the fact that ultimately we’re animals, with a brain built for ensuring we do two things - survive & reproduce. As society and the world around us has grown more complex, our brain hasn’t quite kept up. We’re overoptimistic and set goals based on societal norms rather than what actually drives happiness.

Optimism bias (with lots of work by Tali Sharot) is fascinating. Simply, everyone is wired to think they’re going to be more successful, live longer, and get more stuff done than average. This plays out into happiness expectations - we’re programmed to expect life and happiness to improve because this optimism leads to the motivation to get up and get going - rather than sit around and risk get eaten by a lion. Interestingly, this bias has been shown to decrease over time as the compound feedback of reality vs. expectations works to reduce the bias (exactly what we see in the U-curve).

So what does this mean? Simply knowing that you are likely to overestimate future happiness is helpful. Knowledge is power. It can begin to speed up the recalibration process & lower the unrealistic expectations and, almost perversely, increase your happiness by reducing the gap between reality & silly expectations.

Secondly, the other vital thing to remember is to remember that we’re talking about perceived happiness, not the objectively measurable things that we think will make us happy (money, power, status & stuff). These measureable “goals” are often societally driven, and don’t necessarily lead to happiness (more on this in pt2). As such, part of the expectations gap comes from the result that when we hit those objective goals, it can have a smaller, and more fleeting impact on happiness than we expected. We don’t really care about them.

So what?

To bring part 1 to a close, I want to suggest some really actionable things to try that may be able to start closing the gap between what we think will make us happy and what actually makes us happy. Let’s see if we can get better at spotting the errors in our thinking, and work out what actually makes us happy.

Action 1 - think about your thinking & catch yourself when you’re wrong

The good news is, that by simply reading this and knowing about optimism bias, you’re better equipped to spot it happening & change your thinking. I reckon the word “introspection” is going to be the new “mindfulness” in the world of self-help buzzword bingo, but it’s a cool concept. It means to “think about our thinking” - something that humans are uniquely able to do. It allows us to use the more evolved part of the brain (neocortex) to make sense of the more instinctive animal brain (amygdala).

So what do you do? Next time you’re comparing expectations to reality & feeling bad about it - remember that this is optimism bias in action, caused by your animal brain, and likely to be over-stated. Actively think about lower your expectations to offset the bias. That’s introspection. With practice, you’ll make that thought process a habit & you’ll gradually close the gap.

Action 2 - work out what actually makes you happy

Now the exciting part of this is that I don’t know the answer to this yet for me, nor do I know with certainty how to get to the answer. It’s a big part of why I’m writing this & I’m planning to enjoy the process of working it out. A love of learning is one of my values.

What I do have is an idea to start you (and me!) off. Anyone that knows me, knows that I’m a big fan of Amazing If and their book “The Squiggly Career”. The book talks about plotting your career based on your strengths (a combination of what you’re good at and what you love) & values (what matters to you) rather than a focus on “climbing the ladder”. You can absolutely apply this to how you set your expectations of future happiness, not just work.

We know that if you do stuff you’re good at, your strengths, it makes you happy. We know that if you do stuff you love, your passions, it makes you happy. And we know that if you do stuff that’s aligned with your values, it makes you happy. We also know that if you focus on hitting societal “milestones” (getting a promotion, being a homeowner) or stuff (getting paid £x a year, buying that Porsche) it often doesn’t (see the “hedonic treadmill” next time!).

So, here’s a 5 step process to try and re-wire your brain for how it defines expected happiness:

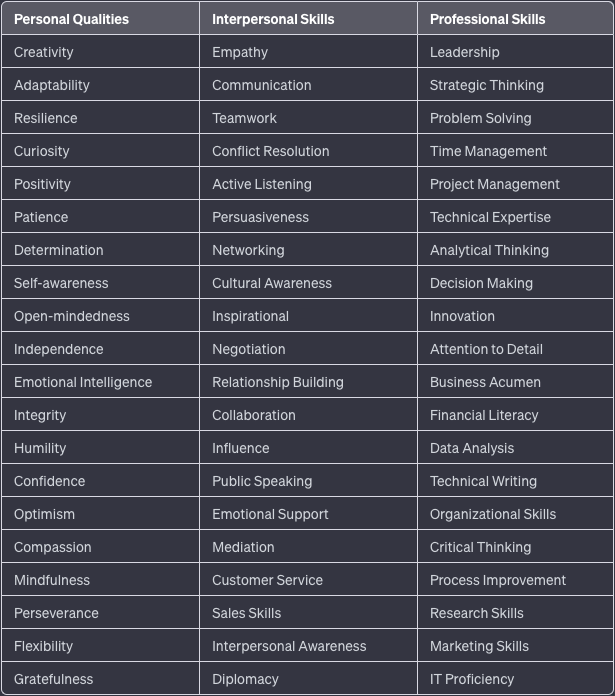

(1) Work out your strengths - spend 10 minutes thinking about what you’re brilliant at. Ask 5 people (friends, family, colleagues) the “when I’m at my best, what do you see?” and summarise them into 3-5 things. Here’s some examples to get you going (thanks ChatGPT!):

(2) Work out your passions - spend 10 minutes thinking about what you love. If that’s too hard, keep a diary and note down the things each day that you loved. Summarise into 3-5 things. They can be activities (e.g. travel) or more conceptual (variety, ambiguity, challenge would be mine!)

(3) Work out your values - I’d really recommend working through the Squiggly Career for this (and for strengths too) to properly get under the skin of this. But an 80:20 approach could be:

Starting with the list below, pick 5-10 values that jump out, add any others

Let’s say your list is “freedom, fun, learning, collaboration” - turn it into a 2 column table with the values in column 1 and “score” in column 2

Start with “freedom” and work down the list asking “which is more important” - give the winner a tick - i.e. first “freedom vs. fun”, tick the winner, then “freedom vs. learning”, tick the winner etc.

Then do the same with “fun” (“fun vs. learning” etc.) By the end, you’ll have built a tally chart that can help you prioritise your list and get from 10 to 3 or 4 values

(4) Re-define success - you can now re-define success as “I’m using my strengths more, because this makes me happy” ; “I’m doing more of the stuff I love, because this makes me happy” ; and “I’m living in line with my values, because this makes me happy”. Then:

Try and make it a bit more tangible - how would it feel this year if I used strengths more / did more stuff I love / lived in line with values? What would this look like? What are the tangible steps I could take to get closer to that?

Summarise it, and turn it into a plan that you can objectively check against at the end of the year (or whatever timeline works for you!). Stick it on your wall, chant it at night - just try and keep referring back to it!

(5) Rationally assess your progress - review the goals you set, see how you did & how you feel. You won’t be able to help the “non-strength / passion / values” criteria creeping in, so use that introspection to really investigate whether it’s your animal brain or the advanced bit making you feel that was

In recommending those steps - I’ve set myself some homework too & will report back on where I get to!

That’s plenty long enough for now - next time we’ll get more actionable as we talk-through the “Neuro treadmills” that stop us being satisfied as we hit goals and the “doom loop” that makes us more miserable because we’re miserable!